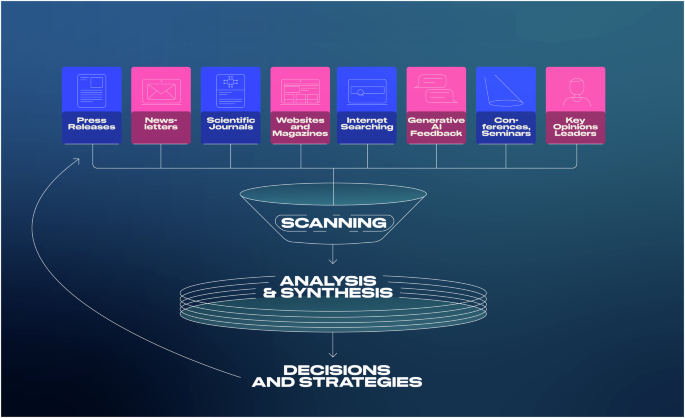

<b id="Fig1" class="c-article-section__figure-caption" data-test="figure-caption-text">Fig. 1: A schematic framework of all the potential sources used during environmental scanning.</b>

Here is a summary of some of the most used futures methods with examples of their use in the medical and healthcare domains.

Forecasting is one of the easiest methods to practice due to the existence of The Good Judgment Project (GJP), a free community site with not only thousands of properly designed forecasting questions but a community of helpful individuals too10.

The GJP was originally launched as a research initiative in 2011 by Philip E. Tetlock, along with Barbara Mellers and Don Moore, as part of a US government-sponsored forecasting tournament. The goal was to see how well ordinary people could predict world events, such as political outcomes, economic trends, and conflicts. The project involved tens of thousands of volunteers who made predictions on various global events and consistently outperformed professional analysts.

Forecasting in this sense is making predictions based on past and present data. What we could mean by forecasting in healthcare is answering a specific question with a probability. Essentially, we design and ask a specific question, and then try to provide a probability between 0 and 100% for the outcome of the question (how likely you think the answer will be yes). Questions could include:

Will the United States’ Food and Drug Administration’s official database contain more than 1500 AI-based technologies by the end of 2026?

Will the global market for wearable health monitoring devices exceed $50 billion by the end of 2026?

Will there be a lawsuit about an AI-based medical technology leading to a patient’s death in any country before 2026?

By performing the so-called environmental scanning (Fig. 1), we can look for studies, reports, news, articles, analyses and data to back our initial probability, which we are always encouraged to regularly reassess based on new findings.

The process involves scanning the sources, analyzing and synthesizing the data, trends, and examples identified from the sources that lead to decisions and strategies.

The Delphi method was originally developed as a systematic, interactive forecasting method that relies on a panel of experts without the negative impact of seniors’ authority on other participants’ opinions. The use of Delphi is prevalent across health sciences research, and it is used to identify priorities, reach consensus on issues of importance, and establish clinical guidelines11.

This method can be particularly useful when analyzing the future of certain medical fields or domains. It has been employed to anticipate the role of AI in pathology within the next decade and primary care in 2029; as well as what digital health competencies should be included in future medical school curricula12,13,14. By iteratively refining expert insights, the Delphi method can also help build consensus on regulatory frameworks for new medical technologies or strategies to address anticipated workforce shortages.

Using fiction to imagine future possibilities offers a powerful, creative lens for exploring potential futures—even for participants who have never written stories before. Vision writing fosters empathy by immersing individuals in the lives of people living in future scenarios. Through imaginative storytelling, it encourages critical thinking, enabling exploration of the interactions between technological, social, and environmental changes. This method not only broadens perspectives but also deepens understanding of the complex dynamics shaping future possibilities.

Writing a news headline in 2034 about a medical technology going berserk; or a press release in 2034 about a medical breakthrough; penning a fictional diary entry from the perspective of a medical student in 2040 using a new technology; and even writing a speech for a politician in 2032 advocating for or against a controversial health policy could all contribute to that by bringing these futures to life. By engaging with these narratives, participants not only envision different scenarios but actively shape their understanding of the possible futures they may one day inhabit.

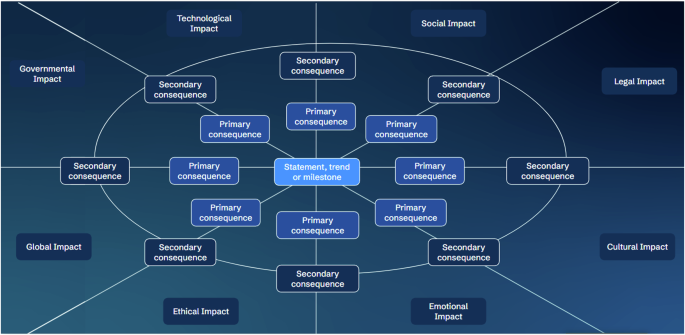

The Futures Wheel is designed to explore the possible consequences of an event or trend. his method uses a visual map to lay out both the direct and indirect effects of a single decision (Fig. 2). The process begins by identifying a central event or issue—like the rise of remote work or a breakthrough cure for Alzheimer’s. From there, primary consequences are mapped, representing the immediate outcomes of the event. These consequences form the first ring of the wheel. The next step involves exploring secondary consequences—outcomes that stem from the primary effects—which create a second, broader ring. To deepen understanding, categories like social, legal, or technological impacts can be applied. Best conducted as a group brainstorming activity, the Futures Wheel systematically identifies risks and opportunities, offering a holistic view of potential futures.

Primary and secondary consequences surround the central event, statement, or issue.

It was used to find the primary and future effects of COVID-19 on eight important dimensions of the health system15. That paper highlighted disruptions in service delivery, medical education and non-communicable disease prevention and treatment; the physical and mental exhaustion of the healthcare workforce; decreased capacity of intensive care units; and increased reliance on telemedicine with a shift in healthcare delivery from hospital to outpatient settings, among others.

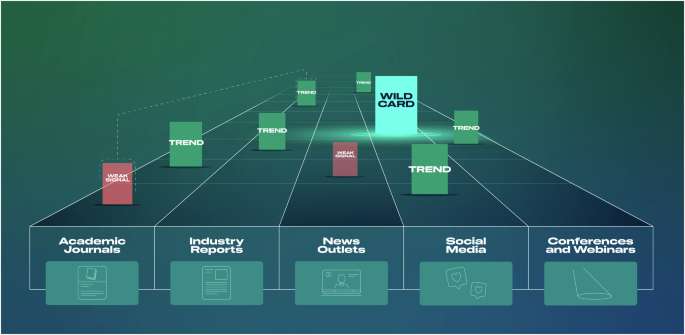

Trend analysis refers to the prevailing directions or patterns of change, and entails assumed developments in the future with a long-lasting effect and impact on a given field. Trends can be identified through data analysis, expert forecasts, and studying historical patterns in medicine and healthcare to help shape future strategies and provide insights into potential developments.

It can be expanded through horizon scanning that provides strategic foresight through identifying emerging trends, technologies, and potential challenges in healthcare to anticipate future developments (Fig. 3). It involves gathering and analyzing data from a wide range of sources to spot early signs of significant change, also called “weak signals”, and evaluating the implications of these changes for healthcare systems and policies. It can also help identify wild cards which are low-probability, high-impact events that can cause significant disruptions. The COVID-19 pandemic or the release of large language models would be typical examples.

While it can be used to find trends, it also helps identify weak signals of change that might happen on longer time frames, as well as wild cards which are low-probability, high impact events of disruption.

Its role in preparing health systems for the uptake of new and emerging health technologies has been discussed in the literature16.

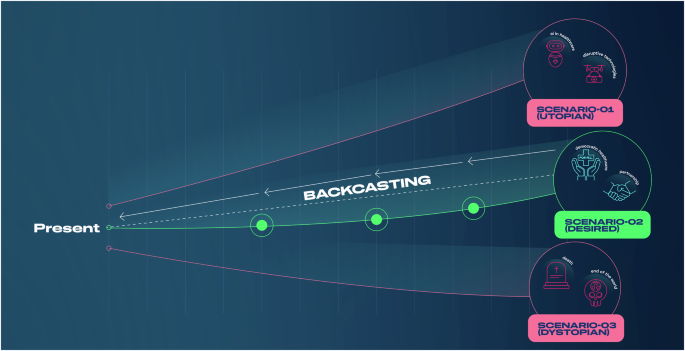

Finally, there are multiple interpretations of scenario analysis, one being the “fairy-tale exercise” (Fig. 4). It helps explore future scenarios by defining a core value that should be maintained throughout scenario development. For instance, when considering the future of medical education in 2040, the value could be the collaboration and partnership between students and professors. A scenario in which this value flourishes is referred to as a utopia (or an idealized, highly favorable future), while its erosion leads to a dystopia (or undesirable future).

It helps create extreme scenarios, as well as the ideal or optimal, the practically achievable future. Through backcasting, it can help identify those steps that are required to have a higher chance of leading to the desired future.

In this exercise, participants describe the characteristics of both utopia and dystopia, emphasizing that one person’s utopia could be another’s dystopia. The predefined value—in this case, the student–professor relationship—serves as the guiding principle for all scenarios. After establishing the extreme scenarios, the next step is to define a middle ground, often called the “optimistic realistic scenario” or ideal future. This scenario represents the desired outcome, but it must be grounded in practical realities. If it too closely resembles the utopian scenario, the features of the utopia were likely not defined with sufficient precision.

The process concludes with backcasting. Participants work backward from the desired scenario to the present day, identifying the regulatory, legal, cultural, technological, or social changes necessary to achieve the ideal future. This method encourages proactive thinking about the steps required to shape desired futures and ensures that the scenarios are not purely speculative but anchored in actionable pathways. This method has been used in the Netherlands for anticipating future pandemic scenarios17.

These are only some of the examples of the over 50 methods medical and healthcare professionals and researchers could use to better foresee how their respective fields will change, what challenges and potential opportunities might arise, and in general, how they can better prepare for the future. Table 1 summarizes ten groups of futures methods and their potential applications in medicine and life sciences.